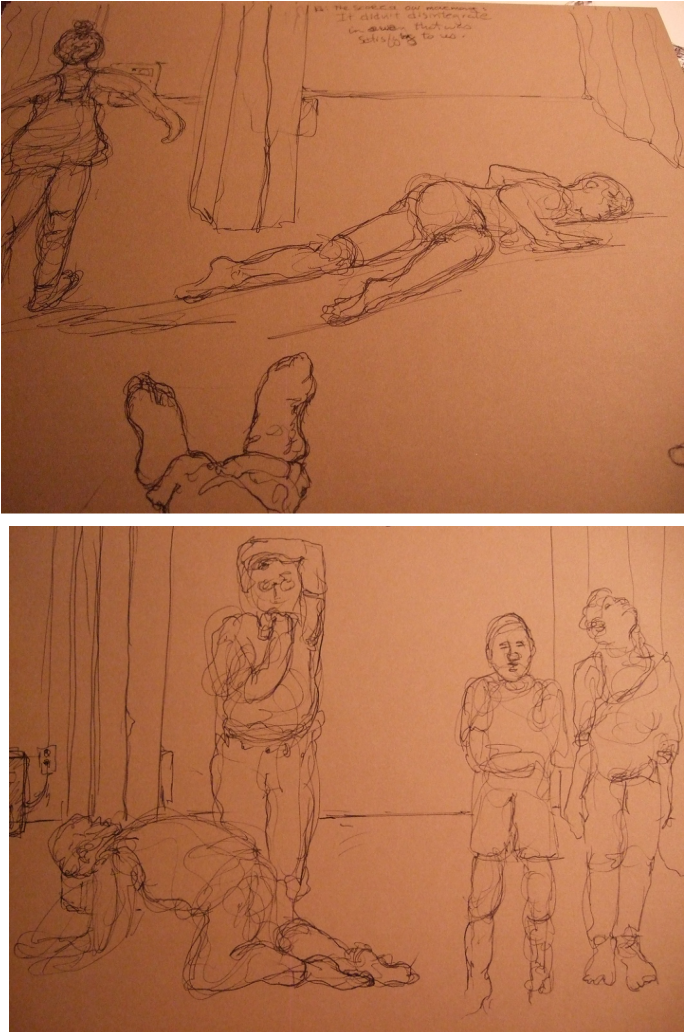

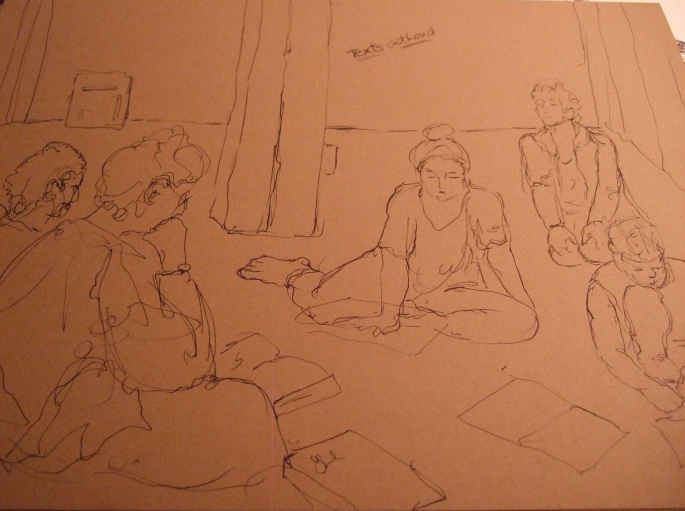

With performances rapidly approaching January 23-26th at the historic Washington Hall in Seattle, we thought it would be nice to share On Cacophony etc. (postscript), written by director Torben Ulrich for Angelina Baldoz and Beth Graczyk on the process for Cacophony for 8 Players.

We also wanted to share that we completed our final residency December 5-8th at Performance Works Northwest as the 2013 Visiting Artists. The support provided by Linda Austin and PWNW this past year has been truly fruitful and nourishing in the development of the work. A huge thank you to Linda, Jeff and PWNW.

Postscript - by Torben Ulrich, April 2013

So, the clock was ticking away, very loud, that afternoon and early evening before we were to skype, before you were going down to Portland. So it became increasingly evident that I couldn’t quite get those things together, those quotes, that at first I had thought about getting in there, or maybe not thought through well enough, since some of them I had not even located properly. There was one about Sahaja, a Sanskrit term, that I thought could come either just before or after the above ending lines, but where was it, and did it really fit, did I remember it rightly etc. So now it’s fast approaching seven, and Molly needed to format it and dispatch it, so I knew I had to let it go, and I thought: well, maybe next time, maybe when you come down in May we can add a couple or three, not necessarily to a piece of paper, but to the net of thoughts…

Then when we had heard from Portland that the four bulkier Players might fit, and we seemed to be on, I asked Molly if she thought it was an idea to add a p.s. to the above and get some of those quotes down on paper, so that we had them in a pile so to speak even before you came, and could use them, more collectively, as a diving board or whatever, down, up, sideways, spiraling (optimally, no splash when you hit the water).

And Molly said why not.

A first move in such a post piece, then, might be a step back, or the Step Back. We used it in the liner notes to the first film from the Lid, a step back from match play, a step back from practice, from running intervals, from weights, from the wall, from the ball, until you get to the step itself and maybe further. We tried to articulate that, Body & Being was the title, remember, the coming together, if possible non-dually, of the physical movement and the mental, the twelves, the grid etc.

The step back, in a different vein, can also be traced back to Heidegger, who said: “The first step to vigilance is the step back from the thinking that merely represents – that is, explains – to the thinking that responds and recalls.”

Then David Wood, in his book entitled The Step Back (2005), took up that theme, under the heading Toward a Negative Capability, a term coming from Keats. In her turn, the nice Korean-American writer called Jin Y. Park picked up this thread from David Wood, in her work called Buddhism and Postmodernity (2008), where she starts chapter 10 stating that Wood “characterizes postmodern forms of ethics as a ‘step back’”:

We also wanted to share that we completed our final residency December 5-8th at Performance Works Northwest as the 2013 Visiting Artists. The support provided by Linda Austin and PWNW this past year has been truly fruitful and nourishing in the development of the work. A huge thank you to Linda, Jeff and PWNW.

Postscript - by Torben Ulrich, April 2013

So, the clock was ticking away, very loud, that afternoon and early evening before we were to skype, before you were going down to Portland. So it became increasingly evident that I couldn’t quite get those things together, those quotes, that at first I had thought about getting in there, or maybe not thought through well enough, since some of them I had not even located properly. There was one about Sahaja, a Sanskrit term, that I thought could come either just before or after the above ending lines, but where was it, and did it really fit, did I remember it rightly etc. So now it’s fast approaching seven, and Molly needed to format it and dispatch it, so I knew I had to let it go, and I thought: well, maybe next time, maybe when you come down in May we can add a couple or three, not necessarily to a piece of paper, but to the net of thoughts…

Then when we had heard from Portland that the four bulkier Players might fit, and we seemed to be on, I asked Molly if she thought it was an idea to add a p.s. to the above and get some of those quotes down on paper, so that we had them in a pile so to speak even before you came, and could use them, more collectively, as a diving board or whatever, down, up, sideways, spiraling (optimally, no splash when you hit the water).

And Molly said why not.

A first move in such a post piece, then, might be a step back, or the Step Back. We used it in the liner notes to the first film from the Lid, a step back from match play, a step back from practice, from running intervals, from weights, from the wall, from the ball, until you get to the step itself and maybe further. We tried to articulate that, Body & Being was the title, remember, the coming together, if possible non-dually, of the physical movement and the mental, the twelves, the grid etc.

The step back, in a different vein, can also be traced back to Heidegger, who said: “The first step to vigilance is the step back from the thinking that merely represents – that is, explains – to the thinking that responds and recalls.”

Then David Wood, in his book entitled The Step Back (2005), took up that theme, under the heading Toward a Negative Capability, a term coming from Keats. In her turn, the nice Korean-American writer called Jin Y. Park picked up this thread from David Wood, in her work called Buddhism and Postmodernity (2008), where she starts chapter 10 stating that Wood “characterizes postmodern forms of ethics as a ‘step back’”:

What Wood identifies as the characteristics of deconstructive ethics – that is, ambiguity, incompleteness, repetition, negotiation, and contingency – stands opposite to the general characteristics of normative ethics and moral philosophy. Normative ethics becomes possible through a clear cut judgment between binary opposites, whereas Wood’s statement is characterized by a refusal to provide such a definitive mode in our ethical imagination. Instead of offering a ready-made recipe to answer our ethical questions, Wood suggests the ethical as a state of suspension. He explains this suspension by using John Keats’ famous expression “negative capability,” which Keats defines as a state “when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.”

Without any irritable reaching: pretty good trope. Negative capability, too.

Refraining as action. A step back as a step of (continued) vigilance. Which way would that be, remaining quiet, would that be back or forth: always being situated in these oppositions (and then, on the dance floor, back or forth being just two different directions, or maybe not even ‘different’).

And then, in terms of time, of temporality, of timing, a step taking time, a step at the right time, traditionally those two, more opposition – as Agamben notes in his work The Time That Remains (2005):

Refraining as action. A step back as a step of (continued) vigilance. Which way would that be, remaining quiet, would that be back or forth: always being situated in these oppositions (and then, on the dance floor, back or forth being just two different directions, or maybe not even ‘different’).

And then, in terms of time, of temporality, of timing, a step taking time, a step at the right time, traditionally those two, more opposition – as Agamben notes in his work The Time That Remains (2005):

Kairos and chronos are usually opposed to each other, as though they were qualitatively heterogeneous, which is more or less the case. But what is most important in our case is not so much – or not only – the opposition between the two, as much as the relation between them. What do we have when we have kairos? The most beautiful definition of kairos I know of occurs in the Corpus Hippocraticum, which characterizes it in relation to chronos. It reads: chronos esti en ho kairos kai kairos esti en hō ou polos chronos, “chronos is that in which there is kairos, and kairos is that in which there is little chronos.

The other day, or maybe a couple of weeks ago, when we revisited at the Yerba Buena, seeing some of that Shen Wei work, with perhaps 22 dancers on the floor of the ‘stage’, and us folks, the public, milling around on same stage, in between them, I thought perhaps that might be an example of chronos in which there didn’t seem to be much kairos. (But to be fair, going back to my childhood, the Danish ballet, the elves, the trolls, the princes, perhaps not a great abundance of the kairological there either.)

So the step back, in chronological time, from here to Denmark, linking up with Hans Beck, with Bournonville, with Andersen, we come to Kierkegaard, a primary ancestor to try, impossibly, to live up to, right here, in this context, his connection to the Royal Theater, the frequent visit to the ballet, his language of the leap, the moment, the right moment, the landing, the passion, lidenskab, repetition, paradoxality, the stop, standsningen, silence, trembling, the works of love: staying with the kairological, how our task would also be, in Portland, to make a fabric of these terms, not as terms, rather voicings, rasas, rhythms, rags. Not as terms, rather as timings.

David Wood, again, links some of these elements together in another book, Time after Time (2007):

So the step back, in chronological time, from here to Denmark, linking up with Hans Beck, with Bournonville, with Andersen, we come to Kierkegaard, a primary ancestor to try, impossibly, to live up to, right here, in this context, his connection to the Royal Theater, the frequent visit to the ballet, his language of the leap, the moment, the right moment, the landing, the passion, lidenskab, repetition, paradoxality, the stop, standsningen, silence, trembling, the works of love: staying with the kairological, how our task would also be, in Portland, to make a fabric of these terms, not as terms, rather voicings, rasas, rhythms, rags. Not as terms, rather as timings.

David Wood, again, links some of these elements together in another book, Time after Time (2007):

What Heidegger attempted to do in the early 1930s and in Being and Time was to conceptualize ontologically precisely the experience of kairological temporality in primal Christianity, which now became the paradigm of all experience for Heidegger. … Here we come across the sources of many basic Heideggerian terms: e.g., the “kairological character” of experience, the moment (Augenblick), repetition (Weiderholung), “wakefulness,” keeping silent (Schweigen), the passion (Leidenschaft) of temporal enactment and the inauthentic time that involves idle talk and the calculative awaiting of a fixed future.

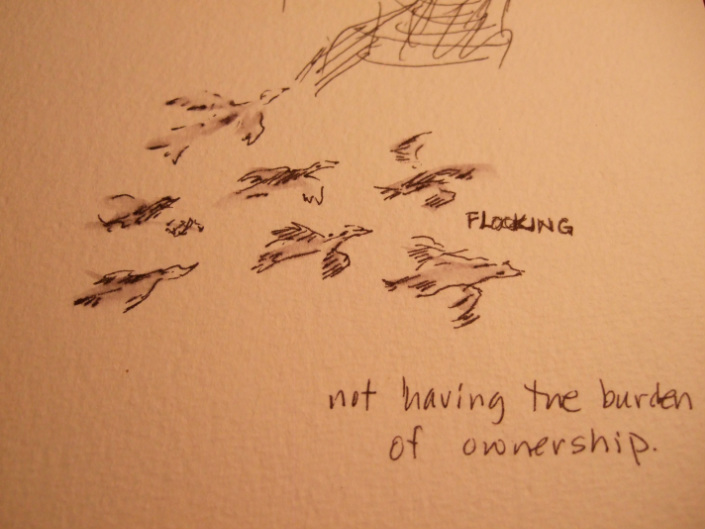

The passion of temporal enactment. The possible passion in the inter-enactment of eight players, dead, alive, in between. David Wood, in that same book, has an interesting concept he calls ‘time-shelters’, and in a certain way, maybe that would fit here a little bit how I could also conceive of the sculptures, and ourselves, the eight of us (or nine or more), the various ways we are composed, complexities of memories, metabolisms, markers of time, pulses of mind, gut, skin…:

What is a time-shelter? Let me offer an account in a somewhat queer key: the universe as a whole is entropic. Human beings, however – indeed, all living beings – are essentially negentropic. In the midst of growing disorganization, we find creatures that consume and manufacture organization and complexity, whether at the molecular level or that of information. These frames generate internal boundaries within the world, ones that both establish and mediate the relationship of inner and outer. …

This phenomenon of sheltering has enormously wide ramifications, but I would like to clarify its significance before offering some illustrations. Shelters are persistent forms of event-discontinuity in the world. They manage the boundaries of inside and outside by representing the outside within; by translating, buffering, and anticipating that which impinges; by resistance, accommodation, expansion, and exchange; and by establishing for these purposes rhythms, rules, and regularities.

So, he says, the outside within, the boundaries of inside and outside, we are still a little in that two-some landscape, the ins and the outs, then within these there are new boundaries of number, eight players, four levels, nine Muses etc. But we’re still trying to come up with one coherent work, aren’t we, that cacophony for those players. I was thinking of those words from Jean-Luc Nancy above, where he counts the Muses and ends up with what he calls the singular plural, I always thought that was a useful term: not a single conception, but after nine nights, before the divine order:

The Muses are daughters of Mnemosyne – not in a single conception, but after nine nights spent with Zeus – and they carry the memory of what comes before the divine order.

In a sense, there is a privilege of art here. But it is the privilege of an index, which shows and touches, which shows by touching. It is not the privilege of a superior revelation. The most difficult thing, no doubt, in talking about art is to move the discourse away from a sacred reverence or a mystical effusion. This is what we must begin to do through an obstinate return from the discourse on “art” to the discourse of its singular plural. For the plurality of the arts must finally make perceptible a fundamental double law.

A fundamental double law, let me get back to that one. But before we wrap it up (and now the clock’s heard ticking again), I came across this fragment which we hadn’t looked at before, I think, on the nine, nava, rasas in George E. Ruckert’s book Music in North India (2004), where he talks about the four and four and “how the first eight moods would leave the audience with a feeling of the ninth, peace”:

Navaras – the nine moods.

karuna sadness, pathos

shringār love, joy

vira heroism, valor

hāsya laughter, comedy

raudra anger

bhayānaka fear

vibhātsa disgust

adbhuta surprise

shānti peace

In a dramatic performance (which includes classical dance), it is felt that a judicious use of the first eight moods would leave the audience with a feeling of the ninth, peace. In a musical performance, the first four, and the ninth, find expression in the rāgas, or musical modes. The moods of the other four, that is, anger, fear, disgust, and surprise, are not regarded as inherent in the rāgas themselves, but rather can combine with stage action to create a greater dramatic effect.

Then in a book on Deleuze and Religion, edited by Mary Bryden (2001), there is a piece by Michael Goddard called “The scattering of time crystals: Deleuze, mysticism, cinema”, where Goddard quotes Michel de Certeau who has some good lines, I think, on “somatisation” etc. I thought of adding those lines in particular hearing of that exiting news that Angelina would join the Players, so to speak, and embody, somatise, articulate, express, both the compositional and the choreographical orders:

What de Certeau can add to this discussion, in proximity to the work of Deleuze, is an understanding of mysticism in terms of the body and temporality. For de Certeau, not only does mysticism have recourse to a social language whereby singular experiences are returned to the social world from which they originate, at times in the form of a minor language, but mystics are themselves the embodiment of a spiritual ‘language’, a writing of gestures, movements and sensations, of which mystical writings will only ever be a translation:

The mystic ‘somatises’, interprets the music of meaning with his or her corporeal repertoire.

One not only plays one’s body, one is played by it. [ …] In this regard, stigmata, visions, and the like

reveal and adopt the obscure laws of the body, the extreme notes of a scale never completely

enumerated, never entirely domesticated, aroused by the very exigency of which it is sometimes

the sign and sometimes the threat.

One not only plays one’s body, one is played by it, double dutch, maybe

approaching Nancy and the double law above, the singular plural.

So finally, finally, we get to with within the realm of Sahaja, as mentioned in the beginning of this long drawn, too longdrawn p.s., sahaja (as an adjective) as maybe the realm of the co-emergent not-two, sahaja being Sanskrit for being born (ja) together with (saha), also according to Per Kværne’s book An Anthology of Buddhist Tantric Songs (1986), and where he also talks of sahaja in Western ways in terms of ‘simultaneously-arisen’, the indivisibility of transcendence and immanence, of bliss and gnosis, samsara and nirvana etc., and in addressing the songs in the book themselves, he says ‘once their essential structure becomes apparent: they reveal the nature of the ultimate state through the systematic ambiguity of their imagery’. Then later on he says the following, and I say, again, love you and ask forgiveness for putting you through this long ordeal:

approaching Nancy and the double law above, the singular plural.

So finally, finally, we get to with within the realm of Sahaja, as mentioned in the beginning of this long drawn, too longdrawn p.s., sahaja (as an adjective) as maybe the realm of the co-emergent not-two, sahaja being Sanskrit for being born (ja) together with (saha), also according to Per Kværne’s book An Anthology of Buddhist Tantric Songs (1986), and where he also talks of sahaja in Western ways in terms of ‘simultaneously-arisen’, the indivisibility of transcendence and immanence, of bliss and gnosis, samsara and nirvana etc., and in addressing the songs in the book themselves, he says ‘once their essential structure becomes apparent: they reveal the nature of the ultimate state through the systematic ambiguity of their imagery’. Then later on he says the following, and I say, again, love you and ask forgiveness for putting you through this long ordeal:

… it follows that the sahaja, too, can be personified and regarded as being the highest Person – the Puruṣa – of Indian religion as a whole; and in fact we find a passage in the Sādhanāmālā which describes the Coemergent in explicitly personified terms: “In all directions it has hands, feet, and so on, in all directions eyes, heads, and faces; in all directions it has ears in the world – constantly embracing all that is”.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed